SEVILLE / 7 July 2022.

The recent pandemic caused by COVID-19 has been a catalyst for seeing and thinking about living and working spaces from a different perspective. A clear awareness has been acquired that there are still agglomerations and concentrations of unhealthy uses in the territory, that cities still generate environments and spaces that favour the spread of diseases, and that building materials are used that, in addition to leaving an ecological footprint, are very harmful.

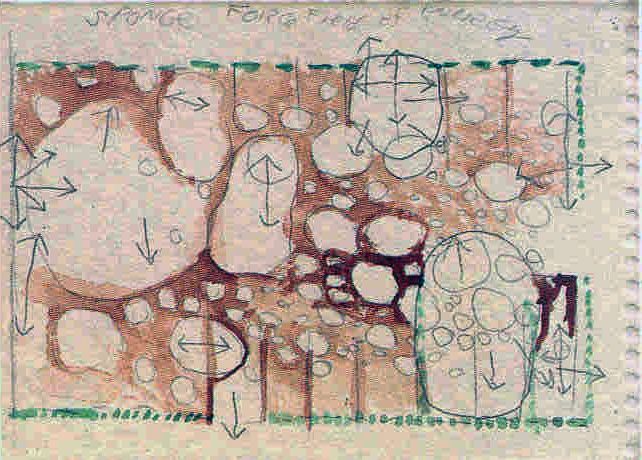

Interaction with the environment defines what human beings are capable of and how they define themselves. The physical environment is identified as a defined place with a concrete organisational structure, used with precise functions within the social environment where human beings live and interact with each other. This environment is configured by a complex artificial epidermis that envelops the human habitat. This epidermis is referred to in building regulations as the ‘envelope’, a term devoid of attributes, as if it were the wrapper of a sweet. However, this third skin complements and completes that of the human organism itself and the textile leather with which we dress. The third skin is designed and configured from and with architecture.

A particular spatial configuration can affect, positively or negatively, both physical and mental health aspects of human behaviour. Perception is not only limited to visual elements, but also encompasses interaction with the other senses and mental cognition. The impact of a space is a function of the degree of control, understanding and sense of coherence that a person is able to experience within it. The way space is perceived is determined by memory, culture, education, beliefs or individual preferences. But spatial perception is also conditioned by the physical and environmental characteristics that shape the environment. Environmental factors simultaneously influence sensory and cognitive aspects of the human being.

Stimulations that affect perception operate both internally and externally, gradually accumulate in bodies and minds, and provide a feedback system of information that leads to the satisfaction or dissatisfaction of people’s basic needs. There are external sensory stimuli such as sound, smell, light, colour, humidity, temperature, etc. and extrasensory stimuli such as air quality, chemical agents, electromagnetic fields, noise, solar radiation, etc. All of them condition, to a large extent, the degree of comfort, quality of life and well-being, and can favour human health; but they can also be the cause of the loss of physical, psychological or cognitive qualities, generating illnesses. Stimulations, physical and mental, can be present in different environments. If they are positive, they should be integrated as health-promoting assets; if they are negative, they should be eliminated because they can produce pathogens.

There are places and spaces that produce certain cognitive symptoms such as stress, spatial and temporal disorientation, anxiety, fear, etc. These are reactions that, as we have seen in previous issues, are perceived more clearly in people with cognitive deficits such as Alzheimer’s sufferers, autistic people, etc. Recent research, carried out in 2019 by the European Network for Brain Evolution Research and the University of Bath, indicates that well-planned environments, in addition to promoting well-being, have a positive effect on decisions and human personality. This work shows that, depending on the experience that the space produces, it can be understood differently, interfering with aspects such as familiarity, the relationship one has with the place or even social relationships. If a particular space can affect the quality of a person’s spatial and social cognition, it implies that living in certain environments can have detrimental or beneficial effects on that person.

There are also physical reactions to certain environments that are better known than cognitive or psychological reactions. These are symptoms that manifest themselves in certain people when they remain continuously inside certain buildings. It is the so-called Sick Building Syndrome (SBS), which consists of a set of complaints whose symptoms are headaches, eye, nasal, oropharyngeal, headaches, lethargy, allergies, etc. It is a syndrome that first came to light in the mid-1970s in offices and schools. Its causes are of varied origin and range from the formal design of the building itself – in many cases hermetic in nature and/or with large glass surfaces – to the implementation of artificial climates, supposedly efficient, or the use of unhealthy materials such as lead, asbestos or fibrillar-type insulation. This discomfort is also caused by products and installations that release carbon monoxide, sulphur dioxide, ozone and even carbon dioxide released by people themselves indoors. In general, they are the consequence of a way of building that has generated and continues to generate pollutant emissions of an environmental, electrical, magnetic or chemical nature.

To combat the symptoms of the sick building, as well as to stimulate the design and construction of assets that favour health in buildings, the Healthy Architecture & City research group of the University of Seville presented, in February 2020, a Decalogue of Healthy Architecture, a compendium of aspects that must be controlled in the design and construction of buildings so that they reach a minimum healthy level. A Decalogue that we will present in the next two instalments when, restarting the next academic year, we will finalise this series dedicated to Healthy Architecture that is having such a great acceptance among the dear public that still reads us.

______

Santiago Quesada-García

Dr. Architect, University Professor, Head Researcher of the Healthy Architecture & City group (TEP-965) and Principal Investigator of the projects ALZARQ of the Ministry of Science and Innovation and DETER of the Andalusian Regional Government.

Post published in the IUACC Bulletin nº 143 of 7 July 2022