SEVILLE / 30 June 2022.

After the small cognitive respite of the previous instalment, we return to the main plot of this interesting series dedicated to Healthy Architecture with a pleasant chapter. We will now show three international experiences that illustrate what the new paradigm of healthy architecture consists of. A model about which there is still no specific theory or scientific systematisation, but which is being defined on the basis of empirical experiences of the architectural discipline when it responds to the demands of groups of people with specific needs.

As we saw in the first instalments of this series, the functional health requirements incorporated into buildings by the architectural avant-gardes of the 20th century –sanitation, safety and accessibility– are, nowadays, unavoidable and are, to a large extent, included in the basic building regulations. However, today’s society demands more from architects than a simple response to functional, technical or programmatic requirements. Designing healthy buildings goes beyond constructing hygienic, aseptic, energy-efficient or zero-emission buildings. The direction is being set by work done for specific user groups. A series of buildings that have planted many seeds over the last forty years, which have borne fruit and shown how architecture can go beyond a simple technical response. In various parts of the world, centres have been designed and built for people affected by cancer, Alzheimer’s disease or residents in palliative care units. These experiences are described below.

One of the most significant examples is the French Unités de Soins Palliatifs (USP) or Palliative Care Units. The challenge faced by the architects who designed the first French USPs was to design a place that would not constantly remind its users of their imminent end. To achieve this, they created an environment, both material and psychological, that would allow the user and his or her family to live with maximum well-being and comfort during the period they would have to live there. To this end they incorporated personalised elements and spaces that allowed the person to express their individuality or sense of belonging. With a defined and contemporary architectural language, the spaces of the USP propose an architecture with a strong symbolism that generates emotion in the people who live there. This model of care facilities for a specific group of people began in 1988 in the town of Villejuif with the USP Paul Brousse, designed by the architects Avant-Travaux, and reached maturity in 2006, when the well-known Japanese architect Toyo Ito built the USP hôpital Cognacq-Jay in Paris.

The second experience to be highlighted are the residences dedicated to Alzheimer’s disease (AD) sufferers. As happened with tuberculosis and cholera at the beginning of the 20th century, architecture is now also being used to alleviate the symptoms of a disease that still has no cure. The first proposals, aimed specifically at people with AD, came about when some buildings began to introduce places for social interaction with the family and other people. The aim was to provoke memories of home and stimulate the memory of the residents. The first institution built specifically for people with AD was the Corinne Dolan Alzheimer Center in Healther Hill (Cleveland), designed by Taliesin Associated Architects in 1985.

At the end of the 1980s, the architectural firm Perkins Eastman developed the Woodside Place residential complex in Oakmont (USA). This building marked the beginning of the development of a housing model for Alzheimer’s patients with innovative design guidelines. It is an architectural typology whose peculiarity is the adaptation and personalisation of the spaces to the users for whom it is intended. A type of building with a reduced scale and size, with a limited number of inhabitants and a simple distribution with studied itineraries and routes. But the fundamental novelty is that they are buildings that have an organisation made up of small cells or dwellings that recreate the atmosphere of the home and are always open to the outside. In addition, the design introduces forms, symbologies and elements that refer to classic mental archetypes that provoke reminiscences in their inhabitants. These buildings also incorporate care services and specific spaces for carers. A new building typology that has given rise to interesting examples such as Boswijk, built in 2010 by EGM architects in the city of Vught (Holland).

Somewhat after the previous experiences, the Maggie Keswick Jencks Cancer Caring Trust network emerged in the United Kingdom. This initiative arose in 1995 from the landscape architect Maggie Keswick Jencks, based on her own spatial and environmental experience when she was diagnosed with metastatic cancer. Maggie’s Centres are the buildings of an association that distinguishes itself by providing practical, emotional and social support, not only to people with cancer but also to their families and friends. Their main characteristic is to do so in buildings that have been specially studied and designed to respond to the emotional needs of these people. They are places where there is no direct medical cure for the disease, although they always arise as annexes to a hospital and at the hospital’s request.

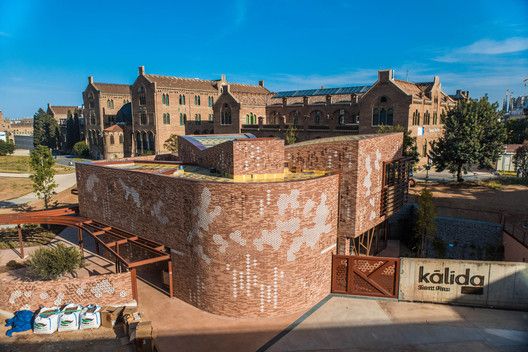

Maggie’s Centres are designed by skilled and committed contemporary architects who use their own personal architectural language in the buildings. In all of them you can recognise the power of the idea that has generated them and the meaning that the architectural discipline brings to a particular place. The architecture of Maggie’s Centres is expressive, artistic and of high quality, creating a sense of space adapted to the specific needs of a particular group. The strong significance of these buildings produces in the patients and their families an identification and a sense of belonging to a group that has the privilege of using these spaces. They are places worth going to and being in. The first Maggie’s Centre was built in 1996, designed by architect Richard Murphy, on the grounds of the Western General Hospital in Edinburgh. There are now twenty-seven centres built in the UK, two in Asia and the only one on the European continent is in Spain, next to the Hospital de la Santa Creu i Sant Pau in Barcelona. It is the Centre Kālida San Pau, inaugurated in 2019 and designed by architect Benedetta Tagliabue.

The common denominator of the three initiatives shown in this issue is the creation of healthy environments, but their main contribution is the construction of meaningful, understandable and recognisable spaces. Places that contribute to the improvement and emotional balance of the people who use them. In the three examples shown, all the buildings propose spaces with a strong identity that are recognised by the people who use them, whether they are healthy or ill, and who also feel welcome in a friendly, non-institutional environment.

The architecture of these buildings incorporates large, naturally lit spaces that convey a balanced sensation through scale, proportion, materials, textures, sound, colours and smells. The layout of the rooms is centred around a comfortable place to stay and rest, to share a coffee or have an informal conversation, a concept far removed from traditional hospital environments. Generally, the spaces are open to the outside, bringing the fresh air into the building, inducing the well-known beneficial effect of the presence of green natural vegetation. Another important aspect is that all buildings ‘take care’ of the caretakers. The spaces used by these workers are studied in detail so that they can carry out their work with maximum efficiency, but at the same time, they can relax properly from the countless moments of stress that they have to live through. Providing these buildings with specific spaces for these workers generates a very favourable psychological environment, as it reduces the environmental stress resulting from complicated situations.

All these buildings have been designed for specific groups of people with illnesses, deficiencies or specific situations, but the findings achieved by architecture to respond to specific physical, mental and emotional needs provide solutions that, due to their efficiency and usefulness, can be extrapolated to the rest of society and, therefore, point in a direction and trace a path to follow for the generalised implementation of healthy architecture in buildings and cities.

____

Santiago Quesada-García, is Dr. Architect, Full Professor, Head Researcher of the Healthy Architecture & City group (TEP-965) and Principal Investigator of the projects ALZARQ of the Ministry of Science and Innovation and DETER of the Junta de Andalucía.

Post published in the IUACC Bulletin nº 142 of 30 June 2022

____

Image of the post:

Centre Kālida San Pau in Barcelona, Benedetta Tagliabue, 2019.