SEVILLE / 3 February 2022.

Well-being and health are intimately linked to the way the human body and mind interact with the environment and how the environment influences the body. Today’s spaces must not only be sustainable, functional and aesthetically beautiful, they must also be comfortable, safe and accessible, but above all healthy. After the notion of mobility, born a century ago with the means of transport; after the ecological and environmental awareness, which arose fifty years ago with the first oil crisis; after the digital revolution, which has been silently taking hold for three decades; the need to build a healthier architecture has arisen in response to an undeniable social demand. A new paradigm is emerging in building, which the COVID-19 pandemic has placed at the centre of international debate.

Cities are places made up of strata that reflect the successive stages of their history. Some authors, such as Beatriz Colomina in her recent book X-Ray Architecture (2019), making an analogy that assimilates disease with destruction, maintain that there is no disease without architecture, nor architecture without disease. The Princeton professor argues that the layers that make up cities are vestiges of urban and social responses to the epidemics that humanity has suffered over time and that the modernisation of architecture in the early twentieth century was a form of disinfection, a purification of buildings. It presents the pioneers of modern architecture as visionaries in the field of health, whose work was a consequence of diseases of the most diverse nature and whose architectural solutions would come to remedy the damage produced by ailments without a cure

Given the current circumstances, this risky hypothesis is still a somewhat biased approach to the state of the question. For it is not true that “man […] has also constructed the conditions of disease”, as Benjamin W. Richardson maintained in 1884. Nor is it true that architecture has dedicated itself to combating disease, because medicine has been the discipline charged with this task. Perhaps the absence of health is confused with disease or the resolution of pathogenic problems of an unhealthy environment with the benefits of designing spaces with a salutogenic approach that benefits the assets that promote health, instead of focusing on resolving what produces pathologies.

Architecture and cities are not the result of medical emergencies, but they have had an important impact on improving the health of the population. This impact has gone unnoticed, perhaps because the cause-effect relationship between the presence of a healthy environment and the absence of disease has not yet been established with sufficient clinical trials.

In the last century, the contribution of architecture to health has been and continues to be to design environments capable of promoting and reinforcing people’s physical and emotional health, through the construction of spaces that avoid harmful, unhealthy or unhealthy situations, thus preventing illnesses. The architectural discipline has generated a progressive well-being and improvement in the quality of life of human beings, favouring the creation of assets with which to have better defences against pathogenic elements. A prime example of this is the introduction of rooms dedicated to bathrooms and kitchens in dwellings. From this perspective, architecture has shown that it is one of the main agents in the care of human health.

In the Healthy Architecture & City research group we have been working, since 2016, on studying the influence that the design and construction of buildings has on people’s physical and mental health. That is why, as the group’s contribution to the IUACC’s weekly newsletter, we want to share some thoughts on the definition and meaning of what is meant by healthy architecture.

To this end, from this first post until the summer, we will publish seven more instalments that will successively explain the genesis, development and status of an emerging paradigm. In the next one, we will begin by recalling the hygienist movements of the 19th century, the postulates of the Modern Movement, the conclusions reached by the last CIAMs and we will end with the seed planted by Kevin Lynch with his work on the city in 1960. The third instalment will cover Ian McHarg’s important contribution on the need to map the spaces of health and illness (1969); this instalment will also refer to the emergence of the concept of salutogenesis, coined in 1979 by the physician and sociologist Aaron Antonovsky. The fourth post will describe the birth in 2003 of a new discipline: Neuroarchitecture. The next collected post will present three examples of contemporary initiatives and buildings, built in the last thirty years. Cases in which architecture has taken into account not only the essential technical and functional aspects, but has also incorporated the previous contributions and integrated symbolic, cognitive and emotional elements that have an impact on the physical and mental health of its users. After this tour, we will end with a decalogue of basic criteria for designing healthy architecture. With a view to the future, the eighth issue will present the five points or fundamentals that an environment, building or city has to comply with in order to be healthy.

——

Santiago Quesada García is Doctor of Architecture, Professor of the Department of Architectural Projects, Head Researcher of the Healthy Architecture & City group (TEP-965) and Principal Investigator of the projects ALZARQ of the Ministry of Science and Innovation and DETER of the Junta de Andalucía.

Post published in the IUACC Bulletin nº 123 of 3 February 2022

——

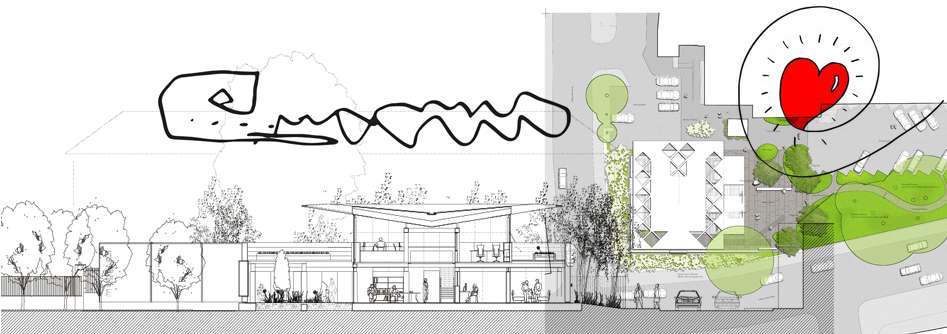

Image of the post:

Maggie’s West London Centre, London, (2008).Rogers Stirk Harbour + Partners.